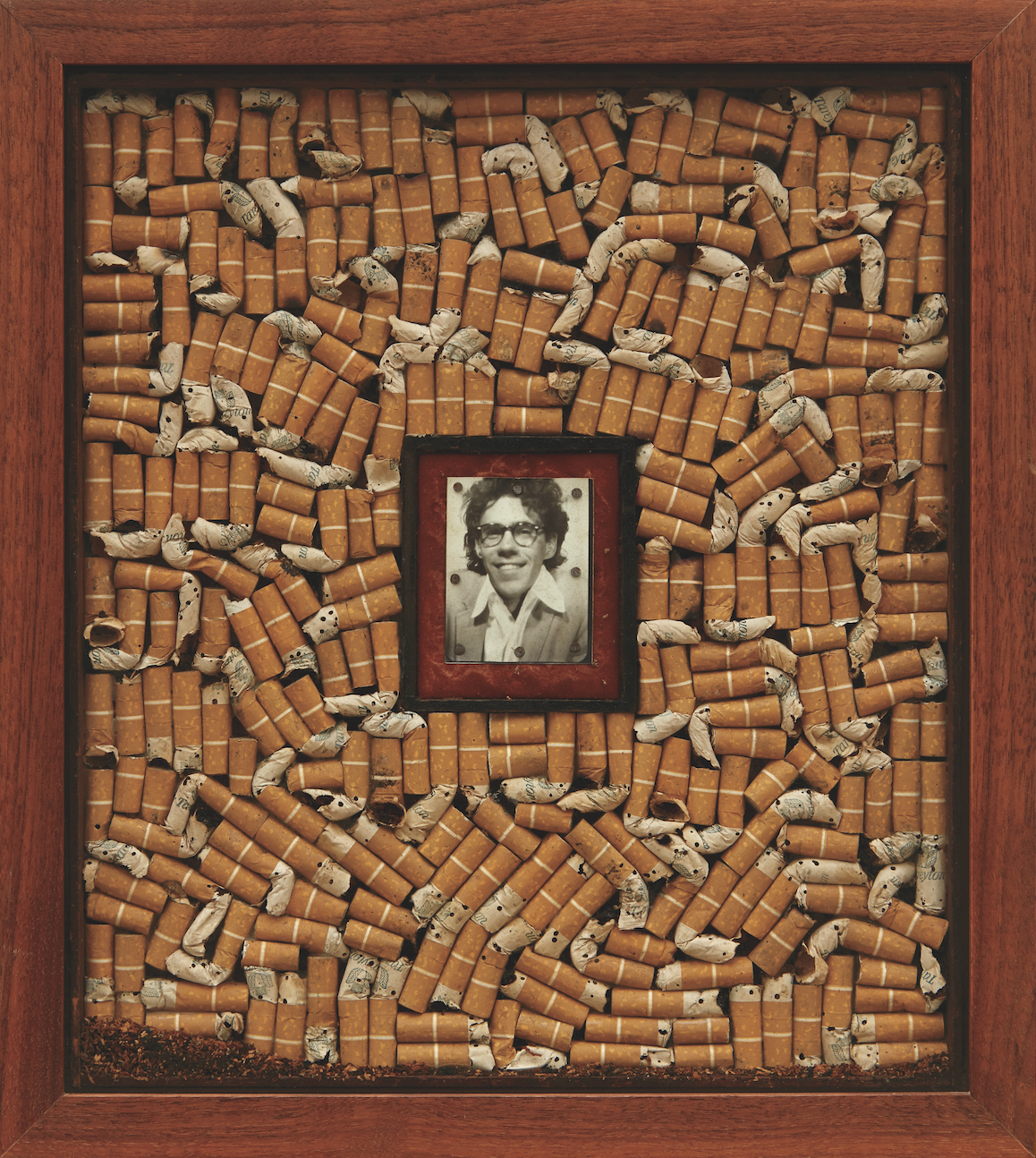

The Winter 2025 issue of Bookforum is out now! This edition features Audrey Wollen on Joy Williams’s stories of angels, demons, and the fate of humanity; Hermione Hoby on narratives of marriage and its dissolution; Jessi Jezewska Stevens on Ágota Kristóf’s confounding fictions of exile. On the cover is artist and poet Joe Brainard’s 1968 watercolor collage, Pansies, accompanying Andrew Chan on Brainard’s letters to friends, lovers, and fans. Also in the issue: Jamie Hood on Virginie Despentes’s Dear Dickhead, Ariana Reines in conversation with Emily Witt, Anahid Nersessian on John Kelsey’s I Forget, Mary Turfah on Isabella Hammad’s Recognizing the Stranger, Lizzy Harding on Elaine May, and much more. Subscribe or renew your subscription today to receive the print issue and support Bookforum.And consider making a donation or gifting a subscription.Thank you, as ever, for reading.