In 1999, I spent my eighth-grade spring break with my mother, visiting my aunt in Rockville, Maryland. In a never-repeated experiment, my father and younger sister went on a separate vacation to Disney World. While they rode the Tower of Terror, we spent our days on the clean, empty Metro as my mom, who had lived on O Street during her first marriage in the 1970s, showed me around the city. One afternoon we went to the Tower Records in Foggy Bottom, where I found Jesus Saves by Darcey Steinke. Its yellow cover bore a black line drawing of a

- review • October 29, 2014

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2014

There are two versions of Charles D’Ambrosio running through this important essay collection, the first book to appear from the noted short-story writer since 2006. First, there’s literary journalist D’Ambrosio, whose job it is to visit peculiar places like hell houses, modular homes, and petty-crime scenes and have thoughts about them that are probably more interesting than they deserve. You don’t really care, reading this D’Ambrosio, how he got to be this thoughtful, conscientious, erudite, and so forth—you’re just glad he did. Second, there’s the D’Ambrosio who, across several essays, goes ahead and tells the story of how he got

- review • October 22, 2014

For all its advantages, the novel must cede ground to the short story when it comes to capturing the contemporary idiom. A great story collection, and Justin Taylor’s Flings is a great story collection, swoops through the world like a butterfly net capturing not only the way we speak but the way we think.

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2014

These days, comic-book enthusiasts are often portrayed as somber scholars, and feminists get caricatured as obsessive eccentrics—so it’s natural to wonder when, exactly, the world went topsy-turvy. A mere glance at photos of suffragettes marching proudly in the streets in 1917 can incite a feeling of liberation vertigo: Where did the last century go? Women’s rights entered a swirling comics-style time tunnel and emerged looking more like a fanatical hobby. Meanwhile, creating superheroes was transformed from a down-market, and definitely obsessive, side project into a handsomely rewarded higher calling.

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2014

I came of age during the perfume-averse ’90s, when the world was still reeling from an overdose of Poison the decade before and had therefore decided that it was better not to smell like anything, or to smell very slightly lemony. CK One, the unisex fragrance with that memorable tagline, offered men and women alike the pleasing anonymity of air-conditioned air pumped into a nice hotel. It was also maybe OK to smell like nature, or some slightly candied replica thereof, but if someone had complimented teen me on my Bath & Body Works Flowering Herbs body spray by saying

- review • September 29, 2014

Years ago I led a seminar on Korean literature and wanted to show a film to the mostly non-Korean students. This was before South Korean cinema was fully established as the darling of film festival juries and adolescent boys everywhere, so I drove to my local Blockbuster and pulled out the only VHS cover I saw indicating electricity had found its way to Seoul. “This will give you a glimpse into modern South Korean life,” I announced to my class about 301, 302, which did indeed show Seoul as a First World consumerist dream housed within tall, concrete apartment buildings.

- excerpt • September 28, 2014

A key figure in the New American Cinema of the 1960s, Gregory J. Markopoulos (1928-1992) made ambitious films starting in the late ’40s, complex psychodramas and romantic meditations that used symbolic color and rapid montage. In 1966, he began to construct short portrait films in-camera, running a single roll of film stock back and forth so that groups of frames were exposed or re-exposed at predetermined points. But he became increasingly disgusted with the conditions and economies of screening and distribution in the US and left for Europe in 1967 with his partner, the American filmmaker Robert Beavers (b. 1949),

- excerpt • September 19, 2014

In the new essay collection Icon (edited Amy Scholder; published by the Feminist Press), writers discuss their relationships with public figures they’ve idolized, obsessed over, worried about, and been inspired by. Contributors include Mary Gaitskill (who pays homage to Linda Lovelace), Johanna Fateman (on Andrea Dworkin), and Kate Zambreno (on Kathy Acker), among others. The pieces vividly blend biography and autobiography, moving from tribute to confessional and back again. In the essay excerpted here, Justin Vivian Bond writes about Estee Lauder model Karen Graham’s serene and reassuring appearance. The “state of grace” it suggested helped Bond “escape into an image

- review • September 15, 2014

At one point in Jenny Erpenbeck’s remarkable novel, The End of Days (Aller Tage Abend), a woman who is falling to her death thinks of how thinks of how, throughout her life, she had done things for the last time without knowing it. “Death was not a moment but a front,” he thinks, “one that was as long as life.” As in the books of W. G. Sebald, life and death in Erpenbeck’s novel are separated by so thin a membrane as to render both a kind of purgatory. But the coexistence is uneasy—something as immeasurable as death doesn’t seem

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2014

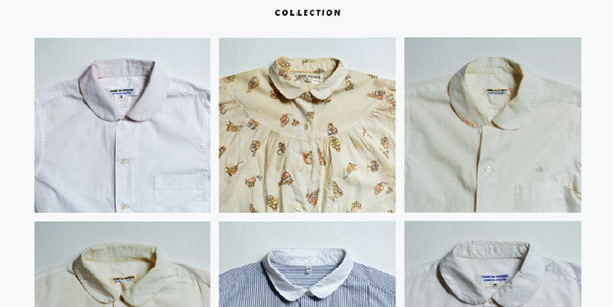

In a memorable scene from Sheila Heti’s 2010 novel, How Should a Person Be?, the protagonist buys the same dress as her friend Margaux, which causes an argument via email: “after we looked at a thousand dresses for you—and the yellow dress being the first dress i was considering—i really was surprised when you said you were getting it too,” writes an angry Margaux. “i think it’s pretty standard that you don’t buy the dress your friend is buying.”

- review • September 10, 2014

Clothes are often written off as a waste of time and energy, something to distract us from what really matters. Yet you have to get dressed—or you do if you want to leave the house. In this way, the question of what to wear—of what your clothing choices express to the world, and what they mean to you—is a fundamental one. And the clothes you pick unavoidably reveal the values and priorities of a given moment, as Emily Spivack has emphasized on her blog for the Smithsonian Museum, Threaded, where she writes about the historical significance of stockings and sequins,

- excerpt • September 8, 2014

First published in 1980, Edmund White’s States of Desire, (recently republished in an expanded edition), is a late-’70s travelogue in which the author candidly describes gay men and gay life in places throughout the US. The book was written at a time when the gay-liberation movement was gaining momentum—helped in no small part by White’s frank and revealing work—and the AIDS crisis was still a few years away. Consequently, States of Desire offers a portrait of gay life in an era of transformation and questioning, of new possibilities and a sense of hope. But old attitudes of homophobia, repression, and

- review • September 8, 2014

Friendswood, Texas, a small town near the Gulf of Mexico, is well acquainted with the apocalyptic. When Rene Steinke’s novel of the same name opens, a hurricane has just devastated the area, and the shift in the water table has pushed a container of rusty-pink corrosive liquid to the surface from its secret home deep within the ground. “Hurricanes come with the territory, right?” local realtor Hal Holbrook says, trying to downplay the climate to a pair of wary buyers. Hal is less willing to acknowledge that virulent toxic waste is just as much a part of the area’s identity

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2013

Ugliness was fun for a while, but then it got too real. After kitsch—which bottomed, or perhaps topped, out in the middle of the last century—came a dark commercial anti-kitsch, an ugly so enveloping and horrid that it couldn’t be celebrated. Mass culture and aspirational brand culture drove right into each other, merging into a hideous beast that vomits Target “designer” lines and QVC frocks and polyester “fleece” blankets in sunny colors. There’s nothing charming about the ugliness that governs how we buy what we live with now. All that’s worse is the production regime under which it’s all made.

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2013

Emmet Gowin, Edith, Danville, Virginia, 1963, gelatin silver print. Smartly designed by Laura Lindgren, PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR (Metropolitan Museum of Art, $50) evokes nineteenth-century photo albums in which loved ones were preserved like flowers under glass. A fine text by Met photography curator Jeff L. Rosenheim effortlessly weaves strands of photographic, political, […]

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2013

Eva Hesse, Top Spot, 1965, tempera, enamel, cord, found objects (metal, plastic, porcelain), particleboard, wood, 82 x 21 1/4 x 12 3/4″ (variable). WHAT DOES A CREATIVE BREAKTHROUGH look like? Can it be something that “abounds with nonsense”? Eva Hesse 1965 attempts to answer this question with a focused, if at times repetitious, study of […]

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2013

Marcel Dzama, The Ditch of the Flatterers, 2007, ink and watercolor on paper, 13 1/3 x 10 5/8″. IN THE EIGHTH CIRCLE of Dante’s hell reside the Sowers of Discord, those who have caused divisiveness in their families, cities, and faiths. The poet, deploying his ever-apt touch with punishments, describes them being sliced and diced […]

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2013

Sarah Sze, Triple Point (Pendulum), 2013, salt, water, stone, string, projector, video, pendulum, and mixed media, dimensions variable. IN A 2010 episode of the reality TV show Hoarders, a woman named Julie justifies her compulsive collecting by insisting that her scraps of fabric, empty bottles, discarded knickknacks, and other Dumpster-dive finds are materials for future […]

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2013

John Horne Burns was the author of The Gallery, published in 1947. At the time, the book was considered a great war novel (less remarked was that it’s also a great gay novel). The book’s publication was widely viewed as the arrival of a huge literary talent and established tremendous expectations for the young writer. What followed, though, was failure on a tremendous scale. On the face of it, David Margolick’s biography of the author, Dreadful (which was Burns’s code word for “homosexual”), is a straightforward chronicle of the man’s rise and fall.

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2013

Romualdo García, untitled (Guanajuato, Mexico), ca. 1910, gelatin silver on glass. Portrait photographs invite speculation, much as diplomatic treaties do when made public. In both cases, the product is the result of undisclosed, expected give-and-take between engaged parties. Their interests were adulterated in a process where agents jockeyed for an advantage, one side maybe losing, […]