The Kim Jong Il that we meet in Adam Johnson’s second novel, set in North Korea, is no cartoon villain, no Team America marionette. He’s a three-dimensional character—a hairsprayed, jumpsuited, hopping-mad monomaniac, sure, but a man in whom we can recognize some of our own jealousies and desires. And although he is offstage more often than not in The Orphan Master’s Son, Dear Leader, as he’s usually referred to, is omnipresent in every conversation, every moment of intimacy, every sorrow that takes place somewhere in this fictional DPRK. He’s the glue holding together not just an entire totalitarian nation, but

- print • Dec/Jan 2012

- print • Dec/Jan 2012

Trinie Dalton Trinie Dalton excels at characters who live and think inexpertly. The main narrator of her 2005 debut collection of stories, Wide Eyed, has bad judgment, isn’t fazed by strange or implausible events, and believes (or wants to believe) in things a skeptic would call woo-woo: talismans, ghosts, mystical signs. Baby Geisha, Dalton’s new […]

- print • Feb/Mar 2012

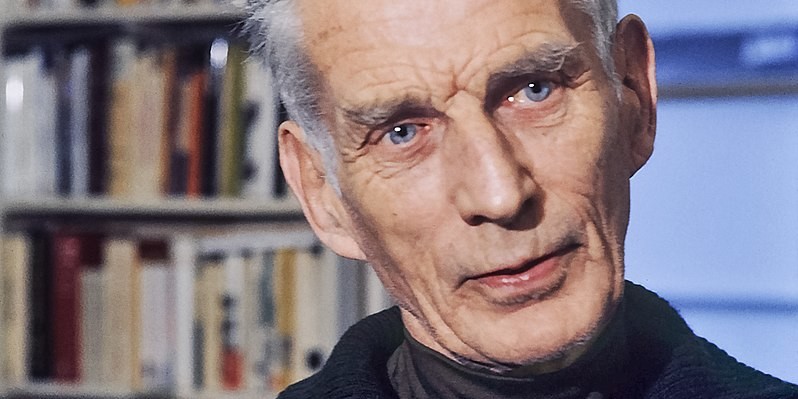

The Letters of Samuel Beckett, 1941–1956, volume 2 of a projected four-part compendium, is an endless Chinese banquet at which all but the most determined gourmands are likely to feel stuffed somewhere between the crispy pig ears and the thousand-year eggs: Some may thrill to the hairpin turns and daredevil high jinks involved in the translation of Molloy from French into English, but many with more than a glancing interest in Beckett may find by page 200 or so that his correspondence and its staggeringly detailed footnotes have, to torture a phrase from Jane Austen, delighted them quite enough for

- print • Feb/Mar 2012

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, New York, 1979–80. From the exhibition “Francesca Woodman,” on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art until February 20. If you are so unfortunate as to be the protagonist of a Heidi Julavits novel, chances are you are both lonely and besieged. You are the girl at the party that […]

- print • Feb/Mar 2012

David Cox, A Street in Harborne. A new novel by Peter Cameron doesn’t do much to announce itself as a literary event. His books are short—only one, The City of Your Final Destination, is longer than three hundred pages—and are not consciously “brainy.” Their chief literary virtues are wit, charm, and lightness of touch, qualities […]

- print • Feb/Mar 2012

It says something about the bewildering reality in the contemporary US that a speculative novelist like Steve Erickson—who has written novels about a dominatrix oracle who makes God her submissive (Our Ecstatic Days, 2005) and a film editor who finds evidence of a primordial scene cached in the frames of a spectrum of movies (Zeroville, 2007)—would spin a variation on the hoary maxim about truth outstripping fiction. In These Dreams of You, Alexander Nordhoc, a frustrated novelist known as Zan, reflects on Bush, the Iraq war, and our black Hawaiian president: “It’s science fiction. . . . Or at least

- print • Feb/Mar 2012

Early in Tom McCarthy’s Men in Space, a Bulgarian football referee–turned-refugee named Anton Markov wonders “how it fits together, how it’s all connected.” In this case, the question is leveled at the twisty network of organ thefts, art forgeries, and black-market lemonade sales that make up the criminal syndicate to which Anton has been indentured. But the same could be asked of this book’s intricate story lines: the circuitous trajectory that Anton’s former neighbor Nick Boardman charts through the Prague art world on the eve of Czechoslovakia’s split into two republics, or of the Byzantine painting that Nick’s flatmate, Ivan,

- print • Dec/Jan 2013

Madeleine L’Engle’s 1962 novel A Wrinkle in Time—one of the best-loved and best-selling children’s books of the past sixty years—was initially rejected by at least two dozen publishers. The story goes that later on, whenever L’Engle attended a literary event, she would carry the rejection letters in her purse. If editors happened to mention to her that they regretted not having had the chance to publish the book, she would whip out the proof that they had passed it up. Like most good stories, this one is probably apocryphal. But it ought to be true, not only because of its

- print • Feb/Mar 2012

Like a science-fiction time traveler or the radio character Chandu the Magician, Satantango is an entity with multiple—or at least two—coequal manifestations, a monument of late-twentieth-century cinema and a modern Hungarian literary classic. There is Satantango the mind-boggling seven-and-a-half-hour movie by director Béla Tarr, and there is Satantango the legendary novel by the movie’s screenwriter László Krasznahorkai, published in 1985 but only now translated into English.

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2012

In Chris Kraus’s novel Torpor (2006), the protagonist Sylvie remarks to an all-male group of intellectuals, including her husband, that there are no women on the list of writers they’re putting together for a cross-cultural literary tour. No one knows any of the “dowdy” lesbians that Sylvie has put forward, so they settle on Kathy Acker. There is little debate. “Of course, thinks Sylvie, if there has to be a woman, Acker would be it. Her books seduce and challenge heterosexual men; her photos just seduce them. . . . Why could the famous artist men be friends, the women

- print • Dec/Jan 2012

T. S. Eliot in Cambridge, MA, 1956. Volume 1 of The Letters of T. S. Eliot, which takes us from the poet’s childhood in St. Louis through The Waste Land, appeared in 1988, the year of Eliot’s centenary; the revised edition, meticulously edited by the poet’s widow, Valerie Eliot, this time with the help of […]

- print • June/July/Aug 2012

Hilary Mantel’s 2009 novel, Wolf Hall, was an extraordinary achievement, a work of historical and artistic integrity that nonetheless managed to be a hit across genders, generations, and sensibilities. I know a twentysomething male worshipper of Thomas Bernhard who loves it, and I know a retired female acolyte of Jodi Picoult who loves it just as much. The book appeared midway through the high-rated run of Showtime’s The Tudors, which grappled lustily albeit ahistorically with the same soapy crisis—Henry VIII’s break with Rome and divorce from Katherine of Aragon in favor of the swiftly disfavored Anne Boleyn—and which, at its

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2012

“I should tell this story the way one should tell this story to one who has never made a bed,” says the narrator of “Sent,” the final missive in Joshua Cohen’s immoderately brilliant tetralogy Four New Messages. He’s describing a bed. Or rather, he’s parodying a particular folktale style of someone describing a bed—a parody into which creep carefully considered anachronisms and authorial asides (“Better to just show the bed! Fairies! Better to roll around on the thing and hear it sing! O spirited sprites!”). In so doing he’s also talking, as he does in each of these stories, about

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2011

John H. F. Bacon, The Wedding Morning, 1892, oil on canvas. Jeffrey Eugenides is used to situating himself between the sexes. He is not quite the author of The Portrait of a Lady in this regard (Elizabeth Hardwick, when asked once to name her favorite American female novelist, wittily answered, “Henry James”), but then who […]

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2011

View through Olafur Eliasson’s 2001 work Viewing Machine at Kistefos Museum, Norway, 2009. When considering time travel, one thinks more often of the metaphysics involved in altering one’s own present condition than, for example, the terrors or joys of inadvertent incestuous sex. But these two concerns can be contorted into one, as if entwined in […]

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2011

A chess scorecard marked with stamps and annotations by Marcel Duchamp, 1919. Americans tend not to get the pleasures of European fiction. If we’re going to read translated literature, we want it Big or Important—Proust, Eco, Sebald, Bolaño—and as for domestic product, blockbuster-driven publishers often seem to prefer flawed big books to flawless little ones. […]

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2011

Adam Gilders Some narrators speak certainly, and others shyly stammer, revealing their stories with reluctance and unease. Think of Moby-Dick, which begins, “Call me Ishmael,” and then consider John Barth’s The End of the Road (1958), which opens on a more jittery note: “In a sense, I am Jacob Horner.” Horner’s nervous squirming came to […]

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2011

In his debut novel, The Art of Fielding, n+1 cofounder Chad Harbach explores baseball as an art that communicates “something true or even crucial about The Human Condition.” Following the career of Henry Skrimshander, a preternaturally gifted college shortstop who falls victim to Steve Sax syndrome (a sudden inability to make relatively simple throws), Harbach unfolds a sequence of stories surrounding the team. We meet Mike Schwartz, the burly captain facing the prospect of life beyond college; Guert Affenlight, the charismatic college president who questions his sexuality as his fascination with Henry’s team- and roommate, Owen Dunne, deepens; and Guert’s

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2011

Peter Gizzi Peter Gizzi’s poems have always walked a line between stylized opacity and friendly, if melancholy, accessibility, enacting an argument about whether language is esoteric or generic, personal or public, our salvation from commerce or hopelessly commodified. This argument is at the heart of much contemporary poetry, but for Gizzi it also represents an […]

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2012

Pity; they used to be such nice girls. Leah Hanwell and Keisha Blake grew up together in a grim housing estate in North West London. They acquired university degrees, good jobs, political convictions, pretty husbands. And they’re miserable. Now in their mid-thirties, they’re pickling in bile and coming apart. Leah has become fixated on a local woman who bilked her out of thirty pounds. She’s secretly taking birth-control pills, scuttling her husband’s plans to start a family. Keisha, who’s gotten posh and changed her name to Natalie, is spending a bit too much time on a website catering to people