“I don’t know why I keep coming back here,” muses Marion Lafournier, the gay Ojibwe man at the center of Dennis E. Staples’s debut novel, This Town Sleeps. He’s talking about Geshig, a small town at the center of the Languille Lake reservation in northern Minnesota. Despite feeling like an outsider as the town’s only openly gay resident, Marion cannot resist the pull to return home. “The first chance I had to move out of Geshig and off the Languille Lake reservation, I took it,” Marion explains. “I moved to the Twin Cities for college. And then as a few

- review • June 17, 2020

- print • Summer 2020

THE TUDOR ROSE ON THE JACKET OF THE MIRROR & THE LIGHT—the final volume of Hilary Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell trilogy, which I’ve looked forward to reading for five long years—has watched me like a cyclops eye since the novel’s publication in March. Or, more likely, I first noticed the emblem’s monstrous quality in early April, when nights in New York grew more cinematically wretched and scary: sleepless, ambulance sirens nonstop. I did, at one point, open the book and read the first page, standing in the kitchen. “Once the queen’s head is severed, he walks away,” Mantel starts, putting us

- print • Summer 2020

WHAT MAKES A PERSON GOOD? We can create a profile using social media and essays published in popular magazines. First and foremost, a good person possesses a deep understanding of power structures and her relative place in them. She has a sense of humor that never “punches down.” She doesn’t subtweet, buy stuff on Amazon, or fly on too many planes. She has children in order to fend off narcissism—a bad quality—and develop a stake in the future of planet Earth, but she would never presume to judge another woman’s choice. And though she occasionally makes mistakes—cheats on her boyfriend,

- print • Summer 2020

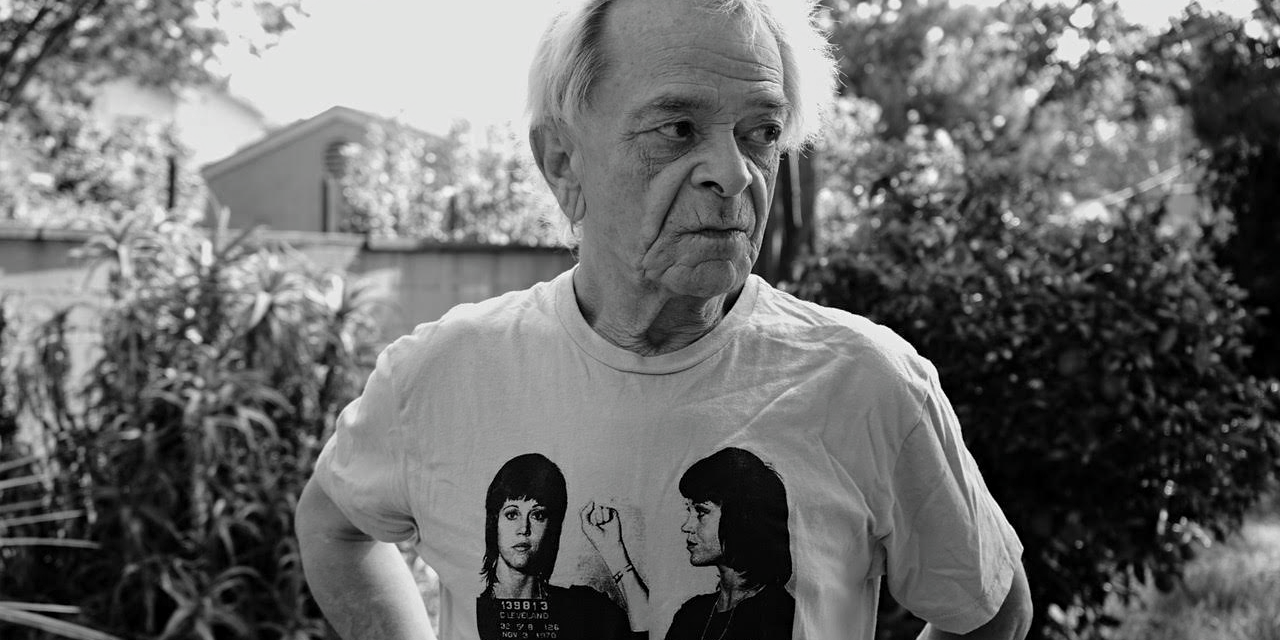

PEOPLE LOVE TALKING ABOUT DENIS JOHNSON, but they do not love talking about his fifth novel, Already Dead. Michiko Kakutani’s New York Times review tagged the book in August 1997, and it has yet to be untagged. She wrote that Already Dead was “a virtually unreadable book that manages to be simultaneously pretentious, sentimental, bubble-headed and gratuitously violent.” Kakutani got flagrant with the kicker, calling Already Dead an “inept, repugnant novel.” David Gates was more generous in the Sunday Book Review, though not enough to overwrite Kakutani. Few writers fell for the book when it came out, and when Johnson

- print • Summer 2020

“WHO CONSCIOUSLY THROWS HIMSELF INTO THE WATER OR ONTO THE KNIFE?” In Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot (1869), Prince Myshkin, the idiot of the title, poses this question to Rogozhin, who is in love with Nastasya. The young woman seems to be in love with both the Prince and Rogozhin, though in The Idiot it’s a bit hard to tell who is in love with who, because everyone is falling in love with each other all the time, and no one will ever admit that she or he is in love, except by way of making fun of the idea of being

- print • Summer 2020

MY FRIENDS’ FACES are hovering in a line of small, burnished tiles. Each square looks alive in a miniaturized way, its own gestural universe, flickering and reflective like sequins from the hem of a dress. We are discussing the end of the world, which means, for us, the fortunate, the end of our habits, the necessitation of new ones. We talk about science, swapping scraps of data with the fervent authority we previously reserved for gossip. “Well, I heard . . .” We talk about ventilators, a new finite resource. There were already so many finite resources, it’s odd to

- print • Summer 2020

“AFFECTION IS THE MORTAL ILLNESS OF LONELY PEOPLE.” So says the unnamed narrator of Horse Crazy, a book about many things, but maybe most vividly the wages of loneliness. A longing for profound human exchange, a communion of flesh and mind, courses through Gary Indiana’s novel, his first. The setting is New York City in the 1980s; the narrator, reluctantly shackled to an esteemed downtown publication for which he writes scabrous and lucid art reviews, pines for Gregory, a beautiful if vainglorious former junkie drowning in self-pity and solipsism who gives the critic suggestive shoulder rubs but denies him sex.

- print • Summer 2020

On my first day in Mumbai, I took a photograph of a proverb pasted inside a taxi door. IT IS EASIER TO FALL THAN RISE, it cautioned.

- print • Summer 2020

He has answered the boy’s questions about condom use, about human nature, and about poo (“the poo-ness of poo”). He has weighed in on the probability of an afterlife (pretty probable) and the pitfalls of having a penis (“Did his penis make him kill people?”). He has explained to him, incessantly, at times impatiently, that “that is the way the world is.” Now Simón, the guardian of David, the boy who might be Jesus, has some questions of his own. I suppose you could call them philosophical. “He, Simón, speaks. ‘I am confused. Did you or did you not tell

- print • Summer 2020

Aside from being in poor taste, exchanging high-fives is no doubt a clumsy business on Zoom, which is presumably how Alfred A. Knopf’s marketing team does its conferring these days. Even so, they must have been agog when The End of October ($28), journalist Lawrence Wright’s alternately sober-minded and gaudy new thriller about a devastating global pandemic, got transformed into the season’s most sensational publishing event by a genuine pandemic’s eruption. Apparently, the publication date did get moved up—Christ, what if they find a vaccine first?—but only by a couple of weeks. Now that the no-longer-so-novel coronavirus has skewed all

- print • Apr/May 2020

Ottessa Moshfegh is known for lacing her fiction with grossness and ugliness, for cursing her misfit characters with repugnant features, antisocial behavior, and a fascination with the nastier bodily functions. “It’s like seeing Kate Moss take a shit,” she told Vice of her writing in 2015. “People love that kind of stuff.”

- print • Apr/May 2020

Twelve years ago this May, then-twenty-six-year-old Emily Gould wrote a cover story for the New York Times Magazine, chronicling her addiction to, and subsequent disillusionment with, what was then still a semi-novel cultural phenomenon: blogging. The eight-thousand-word essay made her the poster girl of the overshare: It was accompanied by a series of moodily lit bedroom photographs that Gould herself described as “vaguely cheesecakey.” “Lately, online, I’ve found myself doing something unexpected: keeping the personal details of my current life to myself,” she wrote in the final paragraph. “This doesn’t make me feel stifled so much as it makes me

- print • Apr/May 2020

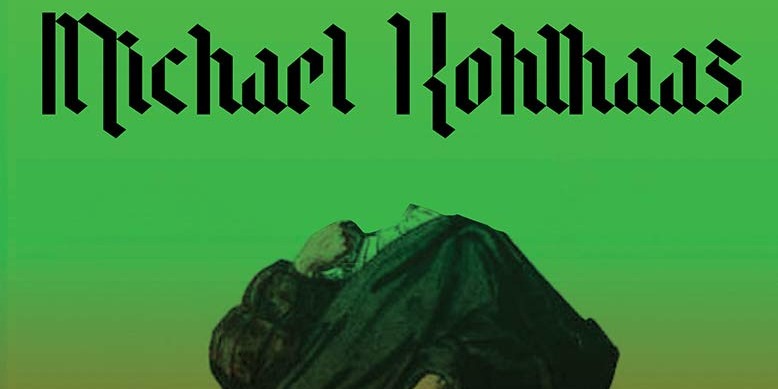

Heinrich von Kleist died by his own hand at the age of thirty-four. For a man whose life was plagued by failure, his suicide was a remarkable success. On November 20, 1811, two months after turning his eighth play over to the Prussian censors, Kleist and his friend Henriette Vogel retired to an inn outside Berlin, where for one night and one day they sang and prayed, composed final letters, and downed bottles of rum and wine (as well as, the London Times later reported, sixteen cups of coffee) before making their way to the banks of the Kleiner Wannsee.

- print • Apr/May 2020

At one point it was my good fortune to spend four summers working in Tuscany, surrounded by its heritage of religious art, and by the last visit, it occurred to me I was in possession of the kind of touristic cultural education I remembered Lucy Honeychurch pursuing in Florence, in E. M. Forster’s novel A Room with a View. Italian religious art plays a role in the plot, especially a scene in which Lucy faints by the Arno, and once I came to recognize the saints’ names and the biblical characters, and the signs that this or that patron had

- print • Apr/May 2020

The characters in Sara Sligar’s Take Me Apart live in 2017, but it would be better to say that they live in “our contemporary moment,” a generic version of the Trump era, a time that artists and writers feel compelled to respond to, usually with “urgency.” They have baby-boomer relatives who suggest they stop trying to be journalists and go to law school. They’re saddled with student loans and credit card debt. They discuss intersectionality at parties and wear fanny packs “unironically.” They contend with workplace harassment and watch Vanderpump Rules reruns. Sligar, it seems, has added all the correct

- print • Apr/May 2020

The next time I’m about to dine on a goat-cheese omelet I will pause to reflect on that first forkful. Images of hens in cramped cages stacked on top of each other, the rain of dung that pours down from the highest to lowest, and the thousands of sun-bright bulbs that accelerate their egg-laying cycles will come between that tasty morsel and my prospective enjoyment. A decision to eschew the omelet and order a salad instead would be a testament to the efficacy of Deb Olin Unferth’s unnervingly vivid descriptions of industrial egg production in Barn 8. Animal rights and

- print • Apr/May 2020

While working as a journalist in Veracruz, Fernanda Melchor came across a report of a body found in a ditch outside a small village. A detail stood out: The victim was a known witch, and the suspect, a former lover, took his revenge when he realized the Witch had cast a spell for him to return. Melchor became fascinated with the story. At first she imagined writing a Capote-esque work of nonfiction about the crime informed by interviews with the suspect and the village’s residents, an In Cold Blood set in Mexico. But in Veracruz, a journalist asking too many

- print • Apr/May 2020

One Thanksgiving during the four years I was a resident of London, at a dinner of Americans and French people, one of the Yanks at the table remarked that if she were a member of the English working class, she “would be throwing Molotov cocktails on the King’s Road and torching Buckingham Palace.” There had been riots in London the year before, student protests were a constant, and the previous autumn had seen the occupation of St. Paul’s, but none of this energy had been directed at the royal family. The Windsors are subsidized at a rate of £82 million

- review • February 27, 2020

Though Hilary Leichter’s new novel Temporary takes place in the world of work, it’s not really about money. Instead, the book regards employment as world forming. It follows a young temp whose one desire is to find a regular job—what she calls reaching “the steadiness.” When she’s not employed, she’s called “temporary”; when she is, she takes the name (and birthday) of whomever she’s filling in for. Though we don’t really have a hero (it’s hard to be a protagonist in a system of self-negation), the story is still a quest narrative: The unnamed temp wants to find the perfect

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

Miranda Popkey’s Topics of Conversation is a novel about the things women (largely women of a certain class) talk about, when alone with each other, when with men, when in the world, and privately to themselves. Stories about ourselves—and how we tell them—are the core of this twisty, prickly, sometimes brilliant debut. Wit is never in short supply here; the narrator is a perceptive observer of her own habit of falling into, and her ultimate inability to accept, a series of stock roles: bright but naive graduate student; professor’s wife; suburban mother; clever daughter; single parent. The fact that she