We all know that men don’t understand women. How could they? Women spend the whole time trying to understand themselves. “I specialize in women,” the writer Nancy Hale said in 1942. “Women puzzle me.” Hale felt that she knew how, “in a given situation, a man [was] apt to react.” (She’d been married three times by the age of thirty-four.) Women, on the other hand, vexed and intrigued her. Her mother, the portraitist Lilian Westcott Hale, made a career of looking at other women, including her daughter. In The Life in the Studio (1969), a memoir about growing up with

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

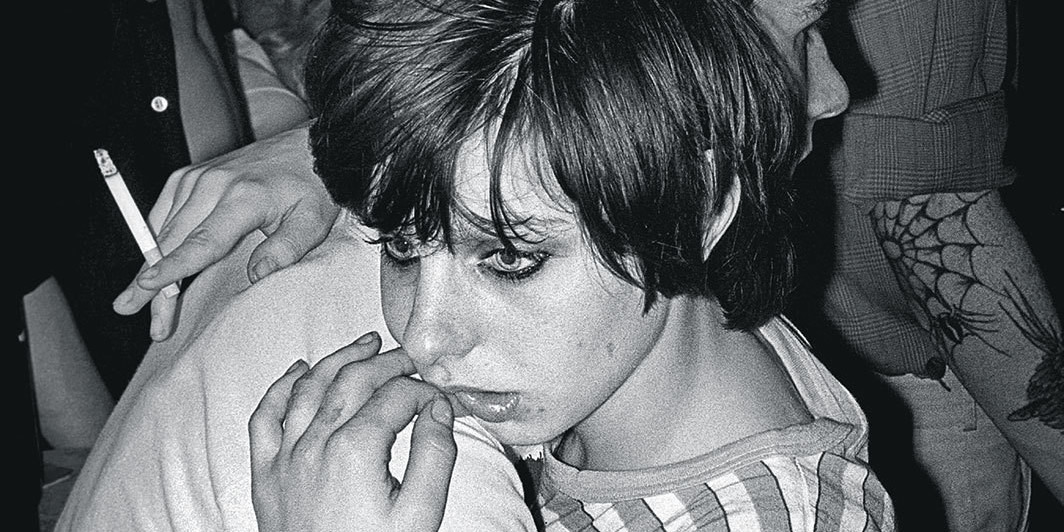

On October 17, 1973, Ingeborg Bachmann—the Austrian poet, novelist, librettist, and essayist—succumbed to burns sustained three weeks prior when she, tranquilizers swallowed and cigarette in hand, lay down to sleep and inadvertently lit her nightgown and bed on fire. She was forty-seven and had, since receiving the Gruppe 47 prize even before the 1953 publication of her first poetry collection, Borrowed Time, astonished the German-speaking public as well as esteemed peers with texts that pushed against tradition and played at the limits of language. She awed the likes of Günter Grass, Peter Handke, Uwe Johnson, Fleur Jaeggy, Elfriede Jelinek, and

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

In the eight years since a small group of anti-capitalist activists set up camp in Zuccotti Park, Occupy Wall Street has generated its own literary subgenre: Jonathan Lethem’s Dissident Gardens, Ben Lerner’s 10:04, Eugene Lim’s Dear Cyborgs, and Ling Ma’s Severance all feature scenes of the 2011 protests. In these novels, the Occupy movement, with its non-programmatic political aims and nonviolent tactics, represents a particularly utopian way of thinking about contemporary revolution—one that is less about direct action than it is about nonaction, about indirection.

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

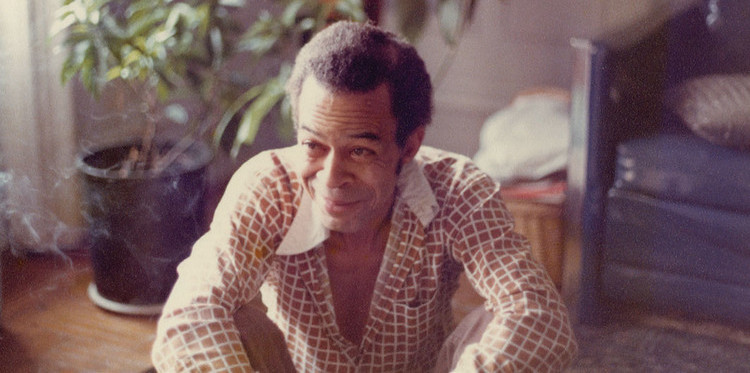

The decades of near-silence that came in the wake of Charles Wright’s trilogy of short novels seem almost as aberrant and disquieting as the novels themselves. Wright died of heart failure at age seventy-six in October 2008, one month before Barack Obama’s election and thirty-five years after the publication of Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About, the last of Wright’s novels, whose 1973 appearance came a decade after his debut, The Messenger. Wright clawed and strained from the margins of American existence for widespread acknowledgment, if not the fame his talent deserved. Cult-hood was the best he got, but it’s

- excerpt • August 22, 2019

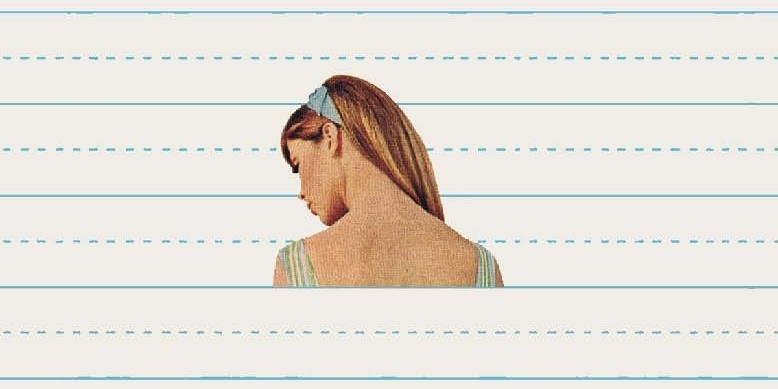

“Little Women was about the best book I ever read.” So began my fourth-grade book report, in 1981. Clear, if uninspired. After one-and-a-half double-spaced pages of cursive rhapsodizing in support of this daring claim, I concluded with the lazy feint of an already overburdened critic: “I would like to go on and on with this report but it would be longer than the book, so if you want to find the rest out my opinion is to read it.”

- review • August 13, 2019

The year is 1927. A schoolteacher who twenty-three years ago showed up with a bicycle and a duffel bag in Thyregod, Denmark, has just lost her husband. Vigand was a cold, pretentious doctor. Once, he could barely be bothered to make a house call on a man who had swallowed his dentures. Vigand knew he was dying. He drove himself to the hospital. He checked himself in, wearing his new gray suit. He told none of this to his wife, twenty years younger and ten times warmer.

- review • August 7, 2019

Today’s challenges of transparency and opacity in everything from the personal to the institutional have created a desire to experience these qualities afresh in literature. I have often thought of these issues as lake-like, because lakes are eerily both. It is a psychic challenge to imagine what cold, still pools of water withhold below a calm, shimmering surface. The work of the Swiss writer Fleur Jaeggy is similarly lacustrine, typified by cool observations that quickly plunge into uncertain depths. Sweet Days of Discipline, set in the 1950s at an elite girls’ boarding school in Switzerland near the Alpine waters of

- review • July 24, 2019

The question that arises whenever a novel is reissued is “why now?” In the case of Suzette Haden Elgin’s Native Tongue, republished by the Feminist Press this month, the answer is evident: First published in 1984—one year before Margaret Atwood’s similarly dystopic The Handmaid’s Tale—Native Tongue is, depressingly, still extremely relevant.

- review • June 26, 2019

There is an oft-quoted line from the Talmud: “And whoever saves a life from Israel, the Scripture considers it as if he has saved an entire world.” Nathan Englander’s latest novel, Kaddish.com, is centered on a son’s preoccupation with saving his father’s soul—not for this world, but for Olam HaBa, or the World to Come. The novel is the Pulitzer Prize finalist’s most humorous and moving work since his best-selling debut collection, For the Relief of Unbearable Urges. Divided into four parts, Kaddish.com follows its protagonist’s transition, from secular, single, cynical Larry to devoted husband, father, and Yeshiva teacher Reb

- review • June 24, 2019

We live in “the Bad Timeline.” It’s a trope you see surface occasionally on social media, especially after some cartoonishly awful thing happens. The idea is this: At some point before Trump was elected or before 9/11 or before Vietnam (pick your generational trauma), reality cleaved in two. In one reality, the Bad Thing was averted. In ours, the Bad Thing happened.

- excerpt • June 17, 2019

A man named Osvaldo Ventura entered a boarding house in Piazza Annibaliano. He was square, stocky, and wore a mackintosh. His hair was grey-blond, his skin flushed pink, his eyes yellow. He tended to smile when he felt uncertain.

- review • June 12, 2019

Ali Smith is writing the world as it happens. In the vein of Charles Dickens, she has set out to reshape the serial form in her Seasonal Quartet of interwoven yet stand-alone novels, responding to the times, not in a mode of reflection but immersion, publishing as she goes. And what times to choose: best of, worst of, as it goes. To say that these have been eventful years, particularly in Britain still in the tenebrous haze of Brexit’s implosion, is beyond understatement. And yet Autumn (2017) and Winter (2018) both circle these political ups, downs, and side to sides

- print • Apr/May 2019

The Clinton Hill brownstone where Kathleen Alcott’s second novel, Infinite Home (2015), is largely set is about as far away from the Apollo program’s Lunar Module—Lem, in NASA-speak—as fictional territory can be. Edith, the elderly landlord of this neglected five-unit dream factory, hasn’t raised the rent in fourteen years and lives in closer communion with the neighborhood’s past than its multi-racial, gentrifying present; the tenants are eccentrics with maladies and psychic wounds that make it impossible for them to traffic in the world outside. One night, when Edith wanders disoriented into the stairwell, they all gather around to try and

- print • Apr/May 2019

Fifty pages into this novel—Susan Choi’s fifth—I was ready to write about it. I understood its design and I admired its execution. So let’s just start there—with what I knew. Two fifteen-year-olds, Sarah and David, attend a prestigious arts school, the Citywide Academy for the Performing Arts (CAPA). Neither can drive, but both can have sex. They fall in love, though this is probably not the right word for what they experience. Their love is colossal. Monstrous. Steamy and feral. They are kids entrained by desire into appearing older and more savvy than they are.

- print • Apr/May 2019

The protagonist of the linked short stories in Bryan Washington’s debut collection, Lot, does not give us his name—at least, not until we have earned this privilege. First, we have to let him usher us through Houston’s working-class neighborhoods and into the lives of queer people of color clinging to their jobs and homes as the city changes around them. The stories unfold in the confines of restaurant kitchens and cramped homes, places where the hard logic of economic precariousness can turn people into enemies just as easily as it can turn them into kin. In Washington’s portrait of the

- print • Apr/May 2019

The most striking scene in Who Killed My Father is also its most emblematic. The French novelist Édouard Louis revisits the memory six times in his brief new memoir-cum-polemic, sifting it obsessively as if for hidden information that the scene won’t yield. One evening in 2001, a preadolescent Édouard stages a performance for his parents and a large group of dinner guests. It’s standard proto-queer kid stuff: a now-dated pop song, fussy choreography, backup dancers conscripted from among the guests’ children, and the ringleader self-cast as front woman. The adults watch politely—all except Édouard’s father, who turns away. His withdrawal

- print • Feb/Mar 2019

Terrible things happen in Kristen Roupenian’s You Know You Want This, a fact hinted at by the table of contents, which reads like a list of YA vampire novels: “Bad Boy,” “Death Wish,” “Scarred,” “Biter.” “I write horror stories,” the author told the Sunday Times last year. “The pull and push of revulsion and attraction is what the book revolves around.”

- print • Dec/Jan 2019

How good was Lucia Berlin? She published her first story in 1960 at age twenty-four, but her debut volume, Angels Laundromat (1981), wouldn’t appear for another two decades; Phantom Pain followed in 1984, and Safe & Sound in 1988; all three came out with small presses. Her readership grew slightly when Black Sparrow Press took her up, publishing Homesick (1990), So Long (1993), and Where I Live Now (1999), but even their support wasn’t enough; nor was the esteem in which Berlin’s terse and minimal style was held by Lydia Davis, Saul Bellow, and Raymond Carver. By the time A

- print • Dec/Jan 2019

Virginie Despentes and Coralie Trinh Thi, Baise-moi (Rape Me), 2000. Manu (Raffaëla Anderson). ON THE NIGHT the French author Virgine Despentes was gang-raped, at age seventeen, she had a switchblade in her pocket but was too terrified to use it. “I am furious with a society that has educated me without ever teaching me to […]

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2018

NO WORKING WRITER believes in the shattering power of an encounter—with another person, with a new sensation, with possibility—more than Amélie Nothomb, the prolific Paris-based Belgian who’s published a novel a year since 1992’s Hygiène de l’assassin (rendered in English as Hygiene and the Assassin, though a more accurate title would be The Assassin’s Purity). Her first book offered an impressive blueprint of what would define her subsequent work: arrogant, infuriating personalities; vicious character clashes; childhood love so obsessive that it bleeds out over an adult’s entire history; and philosophical declarations about war. (Nothomb’s fervent worship of “war,” used to