When you sit down to read a review, as you are doing right now (unless you are standing—in which case, please sit down and take a minute), you rarely have a sense of where the critic is writing from: what time of day it is, what she has eaten, what else she has just read or seen, what’s on her mind. But all of this factors into the work, just as wherever you are as a reader, and how you are feeling, will, too. The pleasure of a critical essay can often be the escape it grants from diachronic time;

- print • Apr/May 2017

- print • Apr/May 2017

Among those who consider themselves serious readers, it’s seen as infra dig to treat literature as self-help. Fiction is not there to teach us how to live or to help us imagine different ways out of our mundane personal difficulties. Nabokov is stern on this in his Lectures on Literature: “Only children can be excused for identifying themselves with the characters in a book.” Any of us who nonetheless persist in, say, taking a novel as a model for our love lives, might hesitate to start with the nineteenth-century Russian canon, unless we aspire to be connoisseurs of suffering. Not

- print • Feb/Mar 2017

Transit, Rachel Cusk’s cerebral and very charismatic new novel, begins like so many of the best stories: with an act of foolishness. Our narrator, fragile, aptly named Faye, goes into debt to buy a crumbling flat. She sends her children to live with their father and embarks on an expensive renovation, infuriating her neighbors, and living for a lonely season in a sort of mausoleum. “Everywhere I looked I saw skeletons,” she says, “the skeletons of walls and floors, so that the house felt unshielded, permeable, as though all the things those walls and floors ought normally to keep out

- print • Feb/Mar 2017

Like many authors—Charles Bukowski, Kathy Acker, Jack Kerouac, Ayn Rand, Philip K. Dick, to name a few—who have attracted cultish followings, H. P. Lovecraft has a biography that feels essential to and inextricable from his work’s singular vision. In Lovecraft’s case that biography is almost unbelievably morbid. He was born in 1890 to parents who both died in mental asylums. Lovecraft himself was a sickly child and lifelong loner. Unheralded at his death at the age of forty-six in 1937, the Providence native published chiefly in small magazines and gained eventual recognition due to the efforts of an early group

- print • Feb/Mar 2017

Almost all of the characters in George Saunders’s first novel are ghosts who haunt Oak Hill cemetery, where their bodies are buried, and the book is told almost wholly in their competing voices. It’s like a play in that it is mostly dialogue, but the novel’s idiosyncratic spelling and typography make the ghosts’ lines seem less like speech than something written or transcribed: a pair of drunken guttersnipes talk mostly in deleted expletives (“st,” etc.), a simpleton’s dialogue is misspelled evocatively (“not to menshun. . . a grate many”). The rules of this version of the afterlife are revealed gradually,

- print • Dec/Jan 2017

Ottessa Moshfegh always wants you to know when one of her characters is ugly, outside or in. The unnamed narrator of “Malibu,” one of the stories in her first collection, Homesick for Another World, fixates on his pimples and demands money from his sick uncle, who has to wear a colostomy bag. “I still had the rash,” he says at one point. “There was nothing I could do about it before my date that night with Terri. I lay on my bed and reached down to the floor and picked little crumbs and hairs out of the carpet.” Terri, his

- print • Dec/Jan 2017

Kathleen Collins, one of the first African American women to write and direct a feature-length work, completed Losing Ground, her second (and final) movie, in 1982, though it did not receive a proper theatrical release until 2015. Loose and effervescent, the film stands as a superb portrait of a marriage between two ambitious members of the creative class. They’re still in love after a decade together, yet strains in the union are beginning to show. Their conversations, with each other and with those in their larger orbit, are about art and ideas—topics rarely discussed on-screen, then or now, with the

- print • Dec/Jan 2017

Zadie Smith’s Swing Time is light by design but as powerful as its predecessor, NW. Where that book vaulted a reader down the block, Swing Time carries you gently to a finish that is bloodless and brutal. The two novels are siblings, rooted in the same slice of northwest London, though Swing Time casts out into New York and West Africa. Themes found in all of Smith’s novels appear: the clash between various Anglophone cultures; a friendship falling out of alignment when only one of the friends hits the big time; and the ways people use each other as markers

- print • Apr/May 2015

My late, much lamented friend John Leonard once wrote, “Satire means never having to say you’re sorry.” I wish John were still around for many reasons, but pertinent to the task at hand, I wish he were here to frame that assertion in the context of Paul Beatty’s audacious, diabolical trickster-god of a novel. The Sellout taunts, jostles, bites your face, and makes so many inappropriate noises at whatever passes for America’s Ongoing Dialogue on Race that it’s practically begging to be batter-fried in acrimony and censure. A scatological narrative submitted with demonic energy and angelic grace (and without any

- print • Feb/Mar 2014

One night in Naples a number of years ago, the mother of an old friend who’d recently expatriated herself to southern Italy from Florence invited us over for a small dinner party. A worldly and glamorous figure under normal circumstances, that night she had her arm in a sling and apologized repeatedly for her cooking handicap. She pressed us giddily on our visit to Naples: the mysterious city built in layers on a dramatically swooping volcanic landscape, filled with bridal shops and treasures of Western civilization neglected in dusty museums, yet seething with hidden, menacing systems of power. Had we

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2016

Early on in Javier Marías’s reputation-galvanizing novel A Heart So White (1992), the narrator, Juan, lies awake on his honeymoon in Havana listening to a couple argue in the hotel room next door. The man on the other side of the wall is a Spaniard, like Juan, and he has a wife back in Madrid; the woman is his tough-talking Cuban mistress. They seem to be hashing out a plot to murder the Spaniard’s wife. Juan’s new bride, Luisa, is also eavesdropping from bed, but she pretends to be asleep. Both Juan and Luisa work as translators at diplomatic congresses

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2016

Shirley Jackson’s legacy might not seem in need of assistance. Fifty-one years after her death, nearly all of her books are in print, and her most celebrated works—“The Lottery,” possibly America’s most famous short story, and the novels The Haunting of Hill House, twice adapted for film, and We Have Always Lived in the Castle, which just went into production after years of stalling (talk about sating a renewed appetite for complicated female leads!)—continue to send chills down spines. In 2010, the Library of America enlisted Joyce Carol Oates to honor Jackson with a best-of volume, and earlier this year

- print • Dec/Jan 2015

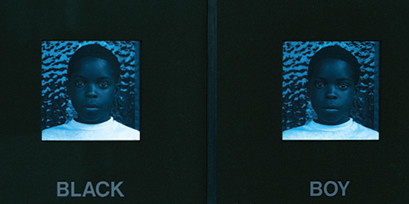

Claudia Rankine’s Citizen is an anatomy of American racism in the new millennium, a slender, musical book that arrives with the force of a thunderclap. It’s a sequel of sorts to Don’t Let Me Be Lonely (2004), sharing its subtitle (An American Lyric) and ambidextrous approach: Both books combine poetry and prose, fiction and nonfiction, words and images. But where Lonely was jangly and capacious, an effort to pin down the mood of a particular moment—the paranoia of post-9/11 America and the racial targeting of black and brown men in those years—Citizen’s project is more oblique, more mysterious.

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2015

Twenty-five years ago, in a review of Abdelrahman Munif’s ambitious “petronovels,” Amitav Ghosh asked why fiction had proved so mute when it came to the momentous story of Middle Eastern oil. Other globally disruptive enterprises—Ghosh’s preferred example is the spice trade—didn’t lack for a robust literary response, like the epic Portuguese poetry that sprang up alongside the discovery of a sea route to India. But the story of fossil fuels had not found its place in serious fiction, despite its tantalizing offerings to would-be chroniclers—its “Livingstonian beginnings” in the Arabian sands, and its “city-states where virtually everyone is a ‘foreigner’;

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2015

Novels set in a medieval past are often fleeing the realities of the present, whether they take refuge in dragon-battling heroism (The Hobbit) or fantastical sensationalism (George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire). This, of course, doesn’t mean that the authors of such books are stuck in the past. Consider Paul Kingsnorth, whose debut novel, The Wake, takes place in eleventh-century England. Kingsnorth has been known for much of his career as an activist, interviewing Zapatistas in Mexico, participating in the G8 protests in Genoa, and, most recently, protesting the damage we’ve done to the environment (his

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2015

In philosopher Simon Critchley’s Borges-ian novella Memory Theater, the narrator, who happens to be named Simon Critchley, discovers the papers of one Michel Haar, “a close friend and former philosophy teacher” who has recently died in a sanatorium after taking early retirement from the Sorbonne. Michel, like one of his heroes, Martin Heidegger, had the long-pedigreed and quasi-mystical idea that poetry can emancipate us from the flat-footed language of philosophy and bring us closer to the truth. This scenario allows Critchley to embark on a tour of philosophical thought and at the same time to tell a fascinating story of

- print • June/July/Aug 2016

“A scurvy thirst awoke him,” begins Lisa Dillman’s translation of Yuri Herrera’s new novel, The Transmigration of Bodies, as though someone had changed her settings to “English (Pirate).” It’s a deliberately confusing effect. Herrera’s short novels observe the violence of contemporary Mexico through a prism of fantasy, and their idiosyncratic language (a jumble of street chatter, high literary style, and archaic formulas) reflects their experimental form. In Signs Preceding the End of the World, he recast a narrative of illegal emigration from Mexico to America—a setting ripe for political dog-whistling and condemnation—as an underworld tale that evokes Dante’s Inferno, the

- print • Feb/Mar 2010

In “Fame,” one of the prose poems from A River Dies of Thirst, the last collection he published before his death in 2008, the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish noted sardonically that “fame is the humiliation of a person deprived of secrets.” Darwish knew fame well; he had been acclaimed from the moment his poems first appeared, in 1960, when he was only nineteen. For the rest of his life, he would be celebrated as “the Palestinian national poet” and “the voice of his people.” One of the ironies, if not the humiliations, of such a role is that the poet

- print • June/July/Aug 2016

It’s late 2009 and Jen, our heroine, has fallen on hard-ish times: She has been fired from her job as communications officer at a Madoff-scuttled family foundation, where she’s been cozily ignoring her true calling (art?) since graduating from college. When she gets bored of rattling around the cardboardy apartment that she shares with her public-schoolteacher husband, Jim, in an inadequately gentrified Brooklyn neighborhood they call Not Ditmas Park, she accepts an assignment from her college friend Pam to paint some portraits. She then allows her work to be incorporated, gratis, into an upcoming installation/performance by Pam, who is an

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2016

Heroin doesn’t sound like heroine by accident. The name for the drug derives from hero, or heroes, as in the late-nineteenth-century soldiers on morphine who fought through their injuries and floated home. The same then-legal morphine was popular among women of the upper classes, who used it to socialize where drinking was considered a man’s game and to survive what they felt to be either their boredom or their subjugation, depending how woke a lady can be while she’s nodding off. Pauline Manford, the rich and inchoate lead in a middling Edith Wharton book, Twilight Sleep, refuses to soldier through