The keen catalogue CONSTANT: SPACE + COLOUR; FROM COBRA TO NEW BABYLON (NAI010 Publishers, $40) inadvertently bathes the utopian artist Constant Nieuwenhuys (1920–2005) in a surprising light. It assiduously contextualizes his mildly bold, tidily irregular paintings, his three-dimensional wire and unusual-for-their-time Plexiglas constructions, and his visualization of “unitary urbanism” (a total human habitat where “life is a game” that merges “the science fiction of social life and urban planning”). Situationist International cofounder Guy Debord christened Constant’s plans for better-living-through-poetry environments “New Babylon,” though Constant didn’t stick with the Situationists for long. There is an affirmative, even (shh!) utilitarian spirit to

- print • June/July/Aug 2017

- print • June/July/Aug 2017

A 2015 PHOTOGRAPH of the Obama family’s Passover seder evokes an irrevocably lost world. In it, we see Alma Thomas’s painting Resurrection, 1966, hanging in the White House dining room. This buoyant artwork was the first by an African American woman to be displayed as part of the permanent White House collection. Tastes and regimes change, but Resurrection now enjoys a position of institutional intransigence—if not assured visibility—in this mansion, which was, as the former first lady reminded us, built by slaves.

- print • June/July/Aug 2017

The unusually striking photograph on the cover of Mary V. Dearborn’s new biography Ernest Hemingway shows the writer in his prime in 1933 sitting on the cushioned stern of a boat, possibly his thirty-eight-foot cabin cruiser the Pilar, and aiming a pistol at the camera. He always carried guns on board to shoot sharks or, when bored or annoyed, seabirds and turtles. He was thirty-four when this photo was taken and he had recently discovered Key West and the fabulous Gulf Stream with its gigantic marlin, sailfish, and tarpon. He fished and fished and fished, insatiable. There were the heroic

- print • June/July/Aug 2017

My first experience of Angela Carter was The Sadeian Woman, her 1979 belletristic defense of the Marquis de Sade as a moral pornographer and protofeminist. Titillating, brilliant, and clearly deviant, it was a perverse introduction to an alchemy of postmodern theory and frankness I didn’t know possible. At twenty, I heavily underlined assertions like this one:

- print • June/July/Aug 2017

In 1954, two dozen people, most of them black, gathered in a small storefront church in Indianapolis. The preacher, a tall, black-haired white man, didn’t launch into a sermon; he asked his congregants a question: “What’s bothering you?”

- print • June/July/Aug 2017

They saw dead people. They heard them too. When summoned, dead people rang bells, wrote on slates, levitated tables. Sometimes their faces hovered in the air. The dead made this commotion for their parents, children, siblings, and friends at the behest of gifted individuals capable of readily communing with the world beyond. If the movement associated with this phenomenon, known as spiritualism—which was popular to varying degrees from the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth century—now appears a quaint relic of a benighted past, we should consider the vigorous currency of aura reading, crystal healing, and psychic consultations. These descendants of

- print • June/July/Aug 2017

THE VIVID DESCRIPTIONS of human suffering in Dante’s Inferno have long attracted visual artists. It’s no surprise that Sandro Botticelli, Gustave Doré, William Blake, Auguste Rodin, and Salvador Dalí all tried their hand at depicting the Italian poet’s demonic landscape. That dark world is rich in dramatic occasion (“an old man, his hair white with age, cried out: / ‘Woe unto you, you wicked souls’”) and irresistibly pictorial (“These wretches . . . / naked and beset / by stinging flies and wasps / that made their faces stream with blood, / which, mingled with their tears, / was gathered

- print • June/July/Aug 2017

WHEN ALICE NEEL PAINTED a portrait of Harold Cruse in 1950, seventeen years before he published The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, she depicted him thoughtfully grazing his cheek with his fingers, his eyes meeting the painter’s gaze with weathered endurance. Part practicality, part protection, this proximity of hand to face—the standby pose of the untested model—recurs frequently in the paintings collected in Alice Neel, Uptown, the catalogue for a recent survey, curated by Hilton Als, culling paintings from the five decades the artist spent in Spanish Harlem and on the Upper West Side. While Neel’s portraits radiate an undeniable

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2017

Around a decade ago, future Obama White House speechwriter David Litt was a contented Ivy League slacker. The breed probably sounds oxymoronic to many Americans, but where do you think the CIA got its most imaginative recruits in the 1950s? Funnily enough, it’s also where postmodern TV comedy shows get their savviest writers today.

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2017

SOUL OF A NATION: ART IN THE AGE OF BLACK POWER (ARTBOOK DAP/Tate, $40), the catalogue for a recent show at Tate Modern in London, covers a period, from the early 1960s through the early ’80s, when Black Power exhibitions proliferated in the United States. Mark Godfrey and Zoé Whitley’s volume is an impressive feat of research, presenting and contextualizing many artists who never became household names. Alongside the well-known photographs of Roy DeCarava, we see a fuller history of the Kamoinge Workshop, including rich gelatin silver prints by Louis Draper, Anthony Barboza, Al Fennar, and Beuford Smith—to name just

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2017

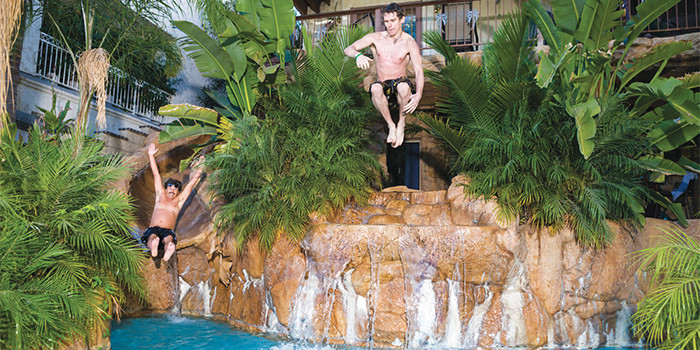

Take it from hedge funder Florian Homm, now a witty fugitive who appears in Lauren Greenfield’s Generation Wealth (Phaidon, $75) hanging out with his bounty hunter pal and his bodyguard: “What you’re sold in this world is a bag of rotten goods. The striving for more and bigger will never, ever lead you to the right place. All of us are following a dream, a toxic dream.”

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2017

THE BIBLE-THUMPING condemnations of pre-Code Hollywood declared its racy films to be wicked enticements cast before innocent eyes. The overheated rhetoric was of a piece with the films themselves: Sin as a showstopper has always proved to be profitable for preachers as well as moviemakers. A preacher of a different sort, Anton LaVey, took cues from both the moguls and the ministers to found the Church of Satan and author The Satanic Bible. From Hollywood, he borrowed the splashy opening—for instance, by ordaining the beginning of the “Age of Satan” on Walpurgisnacht in 1966. With his shaved head and villainous

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2017

FOR THREE DECADES, Lyle Ashton Harris has been producing portraits, collage installations, and other works that demonstrate a voracious approach to art history. He devours photographic conventions and reconfigures them, calling attention to the charged intersection of race, gender, and desire. Harris’s “Ektachrome Archive” includes more than 3,500 personal photographs, made from 1988 through 2001, that display the sensuality and rigor singular to his work; Aperture’s new monograph Today I Shall Judge Nothing That Occurs draws nearly two hundred images from this series. Across these pages, Harris documents intimate encounters, includes photographs of pages from his journals, and captures an

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2017

DURING A CAREER of more than seventy years, Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010) was a consummate insider. For most of that time, she was hardly recognized outside the small circle of the New York art world. That abruptly changed in 1982, when curator Deborah Wye organized a Bourgeois retrospective at MoMA, only the institution’s second devoted to a living woman sculptor or painter. Sculpture suited Bourgeois: Its often-obdurate materials provided a productive counterweight to her forceful creative psyche. But early and late in her career—at first constrained by space, time, and resources, and later by age and infirmity—she embraced the physically less

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2017

IN THE CLASSIC American game show Concentration, contestants vied to clear matching tiles from a board, revealing a larger rebus puzzle they had to decipher in order to secure a win. A new monograph on Katherine Bernhardt serves up a similar play of pictograms. Her pattern paintings offer exuberant blooms of iconography, with titles that conduct a rebus-like arithmetic: Couscous + Cigarettes + Toilet Paper + TVs or Key Boards + Soccer Balls + Avocado + Capri Sun + Headphones. And yet there are no riddles to be solved: The artist’s raucous compositions read more like butt-dialed emojigrams. While this

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2017

There are fifty-five thousand drawings in Frank Lloyd Wright’s archive. Even for an architect so famously aeonian and prolific—he worked ceaselessly from his early twenties until his death, in 1959, at ninety-one—this seems like a suspiciously high number. The inescapable conclusion is that Wright himself created only some fraction of these images. But then who drew the rest? It is often impossible to tell. Making a building is a complex undertaking, and architecture is by nature a sprawling, conjunctive practice. Wright worked with dozens of students, employees, consultants, and collaborators over the years, and their output, too, ended up in

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2017

WHILE RIFFLING THROUGH snapshots with her great-uncle Robert a few years ago, the curator Shantrelle P. Lewis realized that she had never once seen him dressed casually. In the introduction to Dandy Lion, she writes that the sartorial resolve of the men in her family inspired the book’s project, which began as an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago in 2015. Lewis defines the black dandy as “a gentleman who intentionally appropriates classical European fashion, but with an African diasporan aesthetic and sensibility.” The book collects old and new photographs of individuals of African descent in West

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2017

Flushing, Queens, early 1960s, Saturday nights. The boy next door’s name was Eugene; he was overweight, attended the Bronx High School of Science, and was an amateur radio enthusiast. Home alone, a young Ellen Ullman would be watching TV when, “suddenly, Eugene’s ham radio hijacked our television signal—invaded the set with the loud white noise of electronic snow.” In a poignant piece in her new essay collection, Life in Code, Ullman describes how she could hear his voice, and in the sine wave that pierced the on-screen static she could see him, too. His message became as familiar as his

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2017

Andre Agassi’s Open was a groundbreaking memoir for a tennis player when it came out in 2009. The writing had verve and pop, as Agassi (and ghostwriter J. R. Moehringer) opted to tell his odyssey in the present tense, as if reliving every drama. And the confessionals along the way felt truly revealing. Agassi presented himself as a lost man: “I open my eyes and don’t know where I am or who I am,” reads the first line, bringing to mind a tennis-pro Gregor Samsa. We follow him from an intimate vantage point: crying in the shower, enduring militant training

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2017

We tend to think of The Odyssey as the adventure story of Odysseus’s troubled, decade-long journey home from the Trojan War, his path impeded by all manner of men and monsters and gods. And indeed it is full of action and adventure—Odysseus’s wily escape from the Cyclops, his seduction by (or of) the witch Circe, and his interviews with ghosts at the gates to the land of the dead are just a few examples. But as Daniel Mendelsohn, perhaps the most accessible contemporary ambassador of the classics, argues in his new book, An Odyssey: A Father, a Son, and an